Side Tracked: “This Song” and “Pure Smokey”, George Harrison, Thirty Three & 1/3

Even– or perhaps especially– if you’re a huge Beatle fan, you could be forgiven for believing George Harrison simply just stopped making albums after his triple LP All Things Must Pass. Some may even remember that he released Living In The Material World shortly after, but the rest of Harrison’s solo career seems to be blips, maybe a single here or there, “All Those Years Ago”, “Got My Mind Set On You” (why did that ever, ever, get made?), and of course his time with The Traveling Wilburys. There’s a good reason that most of his 70s output gets glossed over like a sterilized re-write of history. Most of it is terrible.

Now I don’t mean terrible in the sense that McCartney was able to craft beautiful melodies centered around what in the world lyrics like “Someone’s knocking at the door, somebody is ringin’ a bell”, or that Lennon spent his whole mid 70s/ “Lost weekend” trying to rediscover what a good melody was. I mean Harrison tried to hard to be philosophical and inaccessible, and his music–and audience– suffered.

He also had a tremendous bout of bad luck. His wife left him (though his own behavior certainly had a hand in that), he tried to record an album, Dark Horse, before his first solo tour and was left with a crippling case of laryngitis that made itself comfortable throughout the album. The tour was even worse, not only was his voice gone, he decided to replace the “she” of “Something” with God, and as many rock stars of the era, had been wooed by the cocaine habit that was exploding around the world. His last album for EMI, Extra Texture, would also be a bust, avoided on radio play except for maybe its lead single “You”.

More problems followed, Harrison was sued for plagiarizing The Chiffon’s “He’s So Fine” in his biggest hit to date, “My Sweet Lord”. When he set about recording his first album off the EMI label, he came down with hepatitis. However, Thirty Three & 1/3 would emerge as one of the best Harrison releases in years.

“This Song” was written as a direct response to the whole “My Sweet Lord” lawsuit, and in a way Harrison predates the MTV craze by concocting a ridiculous video for the affair (you almost can’t hear the song on it’s own and get the same effect) . It’s a meta-moment where he sings about writing the song because of the court, and saying what key the song is (E). He also throws in a bunch of subtle tongue-in-cheek moments (like Eric Idle’s psuedo-feminine declarations before the instrumental break. More than anything, this song proved that the usually dour Harrison was at his best when he didn’t take things too seriously.

“Pure Smokey” on the other hand, was tucked away as the B-side to “True Love”, a Cole Porter cover that is wholly out of place, even on a usual Harrison record. Yet “Pure Smokey” is a delight, sounding more like Steely Dan’s idea of slicked back R&B with some great horn and guitar parts. Strange that it’s supposed to be a dedication to Smokey Robinson when the music doesn’t attempt to comply. It’s an unusual–but well crafted– unknown highlight of Harrison’s catalog.

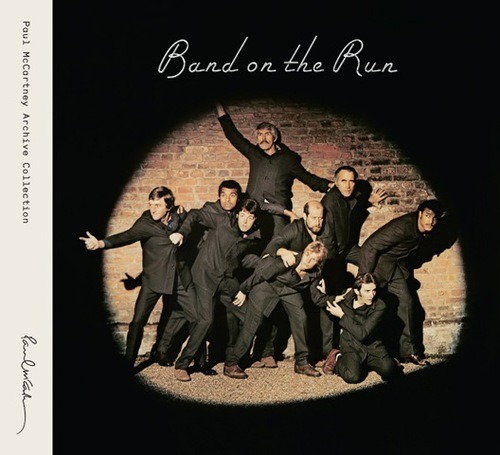

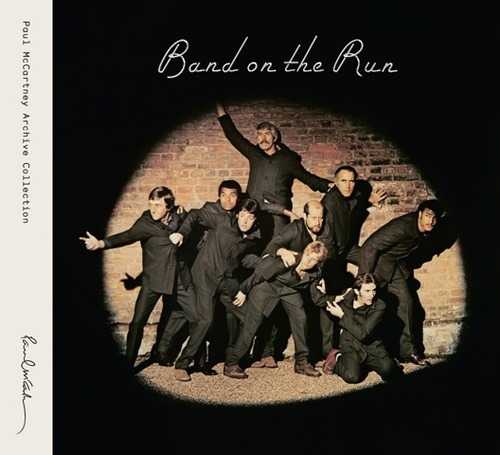

“Mamunia”, Paul McCartney & Wings, Band on the Run

Unlike Paul Simon, Paul McCartney never had a Graceland moment. Perhaps there’s some psycho-cultural reasoning behind it all, but perhaps the idea that McCartney always had a kaleidoscopic melange of musical influences suits it best. Yet Band on the Run has a significant backstory as “the one McCartney recorded in Africa”. However the location of Lagos, Nigeria, was more on the aims of escaping traditions than highlighting old ones.

There are two further anecdotes that obscure worldliness from Band on the Run’s overall sound. One was the oft-noted story of McCartney being mugged coming back from the ramshackle studio with all of the demo tapes in his possession. The other is even more curious; Fela Kuti, by then a well known Afrobeat prodigy, had taken it upon himself to publicly accuse the band of exploiting African music (a similar accusation would befall Paul Simon 13 years later). In response, McCartney invited Kuti to listen to the songs being made at the studio and promised to not use any local session musicians. Still, either as an expression of gratitude, or prevailing influence, “Mamunia” would become the one McCartney foray into African music.

For a man whose lyrics have often been tossed aside as too simple or without meaning, “Mamunia” seems to disprove both. An anglicized approximation of “Mamounia”, the Arabic term for “safe haven”, “Mamunia” is parts an ode to nature and humanity (a narrative that McCartney had approached before in “Mother Nature’s Son”). The rain being both good for the earth, and in the metaphorical sense the harder times that everyone goes through in life. The realization of one’s place, and to be able to embrace it, is what McCartney means by safe haven.

Musically, “Mamunia” is incredibly warm with tightly constructed harmonies, a loping punchy bass line, and a brightly compressed acoustic guitar line, the likes of which could be traced back to “I Will”. McCartney also keeps things interesting by subtle key changes, altering between A major for the refrain and C major for the verses without sounding abrupt.

Lost in the shuffle of McCartney’s effortless melodicism, a term surprisingly used throughout McCartney’s career as qualified detriment, is his ability with arranging harmonies. Even with those less qualified than his former band members, his popular songs in the 70’s would reflect ambitious group harmonies (“Silly Love Songs” is a prime example), on “Mamunia” the harmonies glide between strong unison backing and vocal rounds without skipping a beat.

Yes, it’s an obvious choice for chronicling McCartney’s signature optimism, but “Mamunia” is a singular treat in McCartney’s catalogue, and a strong showing that the man was capable of whatever genre he put his mind to.

“Picasso’s Last Words (Drink To Me)”, Paul McCartney & Wings, Band on the Run

There’s a tremendous story behind Band on the Run, one I might try to tackle some other time, but it is one of the few classic albums where most only remember the obvious songs. "Jet", “Let Me Roll It”, and the title track are bonafide rock and roll staples, and from a historical stance, Band on the Run marks the time where Paul McCartney became post-Beatle. This isn’t to say that the rest of the songs are maligned by bad quality (“Bluebird” notwithstanding) but rather they fit a templete of McCartney singularity rather than only the best whittled down byproducts of being in a group of four.

While Band on the Run would cement McCartney’s chops as a rocker, revisiting this album shows a surprising depth, there’s the jaunty tongue in cheek “Mrs. Vanderbilt”, a missive fired at both messieurs Lennon and Harrison, the vastly underrated and forgotten “Nineteen Hundred and Eighty Five”, African-lite pop ode to nature “Mamunia”, and then there’s “Piccaso’s Last Words (Drink To Me)”.

McCartney chalked up the inspiration from a good natured challenge by Dustin Hoffman. Hoffman had been fascinated by McCartney’s innate ability, begging for insight or explanation as to how McCartney wrote a song. McCartney was at a loss for words to describe it other than jumping from a simple idea or phrase. Hoffman then asked McCartney if he could write a song based on Pablo Picasso’s last words, “Drink to me, drink to my health, you know I can’t drink anymore”, a fact he had picked out of a recent article. In Hoffman’s recollection, McCartney wrote the song’s entirety that very night.

Yet it’s not only the lyrics that make this song so unique and powerful in McCartney’s catalogue. In an era that was a deluge of “pop symphonies”, “Picasso’s Last Words (Drink to Me)” might well truly earn the title. Starting out as a bare acoustic bar room elegy, the music elides through key changes, sound collages, and song callbacks; “Jet” and “Mrs. Vanderbilt”, in a mode very similar to where the Bee Gees would mine success a few years later.

It’s one of those few songs where the changes are so exotic and without warning that it remains a constant pleasure to listen to. It’s not so much a medley as it is symphonic movements channeled through McCartney’s pop vernacular. It would be a disservice to say it’s one of McCartney’s finest, as he’s written too many to narrow it down to a few, but it has all the touchstones of a McCartney masterpiece; a melody so catchy that you begin to hum along before the phrase is complete, the music ornately arranged yet deceivingly simple driven by McCartney’s inimitable lead vocal.

So next time you come across Band on the Run, make sure you don’t miss the deeper cuts for the singles, especially “Picasso’s Last Words (Drink To Me)”.